Buy-to-Let vs Pensions: Which Is the Better Retirement Strategy?

The British public have had a long and sometimes unhealthy obsession with property. For many, bricks and mortar mean much more than a place to live or raise a family, housing has doubled up as a retirement plan, a nest egg, and even a springboard to borrow against for future ventures.

Many of those with extra cash in hand, instinctively turn to buy-to-let. After all, it looks straightforward: own a property, collect the rent, and watch its value rise over time. The appeal is obvious, it’s tangible, feels safe, and the potential for both income and capital growth is easy to grasp.

However, perceptions are one thing, reality is another. The same tangible nature of property that makes it seem so attractive in the first place can have many downsides. Tax bills, maintenance headaches and difficult tenants, can all chip away at returns. This is before we get to the risks that can come from having a highly concentrated portfolio in one, very illiquid, asset class.

An ongoing love affair with property

There’s no doubt that many have made good money from buy-to-let investments. Many assume a great return on investment to be a sure thing. Messaging which promotes buy-to-let is seen everywhere, from traditional media, to advertising and social media. Many seemingly successful ‘influencers’ tout their house flipping lifestyle as a guaranteed way to get rich even if, in reality, they are at least partially funding their lifestyle from courses they are selling rather than the property portfolio they are teaching others to replicate.

At the same time, pensions have been cast as outdated or underwhelming. Stories questioning whether pensions ‘work’ continue to circulate, often fuelling misconceptions about their role in retirement planning.

For those considering buy-to-let’s role in their retirement plan, it is worth taking a look past the noise at the reality of both buy-to-let verses more traditional methods. As ever with investing, there are no absolute right or wrong answers. Yet hard thinking and hard facts are crucial when considering something like retirement, not just news headlines.

Who needs a pension when you have property?

It is easy to see why buy-to-let can feel like an attractive option. Instinctively, people feel that they ‘get it.’ Stories about other people’s buy-to-let success spread fast, but the role that good timing and luck both have is underappreciated. What we don’t hear is the stress and struggle even behind the successes, let alone the countless amounts who have tried and failed to achieve their buy-to let dream.

Taking on high levels of debt to buy additional properties doesn’t feel particularly risky when mortgages are already such a familiar part of homeownership. The psychological security of homeownership has been recognised for centuries, including by Victorin novelist Anthony Trollope, who once said once said:

‘It is a comfortable feeling to know that you stand on your own ground. Land is about the only thing that can’t fly away’

Most people’s understanding of property has developed very little from that time.

Despite the many headwinds the sector has faced in recent years, narratives around future rental demand remain seductive. Populations are growing faster than supply and both decreasing affordability for first time buyers and more people living mobile lifestyles meaning more people are renting rather than buying. Yet yields are always relative to prices and prices are high, not least because many have already acted on this kind of speculation. Before comparing property to pensions, it is worth unpacking what a ‘buy to let’ strategy really involves.

Thinking of starting a business?

Investors could be forgiven for thinking that buy-to-let is comparable to holding money in a bank. After years of rock-bottom interest rates, savers couldn’t generate much of an income even with sizable deposits. Even with recent rate rises, inflation has eaten into savings, leaving their purchasing power over 20% lower than it was two decades ago[1].

This has driven investors to hunt for higher returns, some into riskier bonds or shares, others into property. The perception that moving from cash to buy-to-let is just a short step up the risk ladder is wrong. It leaps from one end of the risk spectrum to the other, particularly if a mortgage is involved.

Borrowing to enter the buy-to-let market is akin to starting a very highly geared (or leveraged) business, with all the costs, tax, compliance issues and risks that go with the territory. Successful buy-to-letting has to be run on such a basis if it is to at least mitigate the very material financial risks that it entails. Those who go into the buy-to-let market without anything more than a rough idea of gross yield numbers, and the belief that house prices always go up will be lucky to get the sort of outcome they are hoping for.

Borrowing to invest cuts both ways

How many investors would walk into their bank and pronounce that they wanted to borrow up to three times the value of their investment portfolio? Those who did would most likely be quickly and politely shown the door. Buy-to-let investors, on the other hand, are asked to take a seat. What seems like madness in one case is considered to be perfectly sane in the other.

While some people purchase investment properties outright, many choose to leverage or ‘gear up’ their capital. Typically, buy-to-let lenders ask for around 25% as a deposit; those who buy a £400,000 house or flat can put down £100,000 and borrow £300,000.

Borrowing to leverage capital cuts both ways. For example, if the property increases in price by 20%, the geared investor in the example above will make £80,000, which on their capital invested is a return of 80%. However, if the market declines by 20% they will lose £80,000 of their £100,000 capital invested. It is also possible to lose more than the value of your initial capital e.g. a loss of 25% would wipe it out. This is the curse of negative equity.

There have been two big UK residential property falls since the mid-1980s starting in 1989 and 2007. Property values – after inflation – fell by over 30% on both occasions.

Table 1: Gearing magnifies losses – effect on £100,000 equity capital

|

Period |

Inflation |

Price fall |

Ungeared |

1x geared |

2x geared |

3x geared |

4x geared |

|

1989-1993 |

Before inflation |

-15% |

£85,000 |

£70,000 |

£55,000 |

£40,000 |

£25,000 |

|

After inflation |

-34% |

£66,000 |

£32,000 |

-£2,000 |

-£36,000 |

-£70,000 | |

|

2007-2009 |

Before inflation |

-22% |

£78,000 |

£56,000 |

£34,000 |

£12,000 |

-£10,000 |

|

After inflation |

-32% |

£68,000 |

£36,000 |

£4,000 |

-£28,000 |

-£60,000 |

Data source: Nationwide House Price Index. Bank of England UK CPI. All rights reserved. Red = negative equity.

Mortgaged buy-to-let investing is attractive because property feels “safe”, it’s a tangible asset that should always be worth something. But this is a misleading view. A diversified, unleveraged portfolio can still experience steep declines, sometimes 30% or more. Yet in the worst case, even a high-risk stock holding can only fall to zero.

With a mortgaged property, smaller price falls cannot just wipe out an investor’s equity but take it into the negative. If this happens at an inopportune time investors can be forced to sell at a loss, or sacrifice valuable years retirement that could otherwise have been enjoyed to the full while waiting for prices to recover. For anyone depending on buy-to-let for their retirement, that’s not just volatility, it’s an existential risk.

Yield figures – not all what they seem

Many investors, particularly those new to the buy-to-let market, are seduced by the gross yields that can be achieved on properties. Promotional materials often boast double digit percentages without much explanation. An example will help to demonstrate:

In 2025, the average gross buy-to-let yield in the UK is around 6% with an average rental of around £1,300 pcm. In turn, this implies an average property value of around £260,000[2].

On paper, the above figures sound attractive. In practice, the gap between gross yield and net yield is wide enough to swallow most of the profit. Investors must either spend time keeping a tight record of their property expenditure for HMRC or spend money on an accountant to do so.

- Initial costs: Stamp duty (rates of which are higher for second properties), legal fees, surveys, and mortgage arrangement charges are just the beginning. Many landlords also face early repair work, furnishing expenses, and mandatory safety certifications before the first tenant moves in.

- Ongoing costs: these break down into annual costs and longer-term amortised costs to cover longer-term maintenance items. Land values may rise and fall, but property on it is a naturally depreciating asset; it falls to pieces, over time, if not looked after properly. Annual costs include insurance costs, landlord cover, and maintenance, furnishings and fittings[3].

For those that buy leasehold, there is likely to be an annual service charge/sinking fund contribution to pay as well as the ground rent on the property. For those who use agents to manage the property, 10% to 15% of the monthly rent is quite normal. Finally, mortgage payments need to be made. At time of writing, a two-year 75% buy-lo-let mortgage rate would probably come in at around 4.5% p.a. with a hefty up-front arrangement fee[4].

While not strictly a cost, void periods where tenants cannot be found or for redecoration are also common and eat into overall yield figures.

- Longer term costs: Properties age, and tenants accelerate wear and tear. Even well-maintained properties are affected by changing tastes which may affect both rental and resale values. Boilers, roofs, wiring, kitchens, bathrooms, and even driveways all need replacing on cycles ranging from five to twenty years. Industry consensus suggests setting aside 30–35% of gross rental income for maintenance and running costs—before mortgage repayments.

While most of the above costs are allowable against tax, landlords are no longer allowed to claim complete tax relief on their mortgage repayments, although a 20% tax credit is available[5].

- Sale costs: Finally, selling a property demands agent’s fees and capital gains tax at the prevailing rate, although if the investor lives in it for a certain period of time, they may be able to deem it to be their primary residence. This may not suit some investors on practical or moral grounds.

So, when some basic numbers are calculated the true net yield is far less compelling than the headline figures. These basic calculations are set out in the tables below[6]. The example uses updated figures based on a buy-to-let, interest only property in Newcastle in 2024, given Newcastle had one of the highest gross yields in the UK last year[7]. Average rents in Newcastle sat at around £1,200 a month with average house prices of a little under £200,000.

Table 2: Assumptions – Newcastle, United Kingdom – 2024 estimates

|

Basic Example |

£ |

% |

|

Annual rent |

£14,400 | |

|

Gross rental yield % |

7.5% | |

|

Occupancy % |

95% | |

|

Property value |

£192,000 | |

|

Investor’s Capital (25% LTV) |

£48,000 | |

|

Interest only mortgage |

£144,000 | |

|

Annual mortgage interest |

£6,480 |

4.5% |

Source: Albion assumptions and estimates 2025 – basic example only. UK Buy-To-Let Yield Map 2024 | Verta Property Group

Table 3: Net yields look a lot less exciting

|

Monthly Budget |

In |

Out |

|

Monthly rent |

£1,200 | |

|

Vacant periods @ 5% p.a. |

£60 | |

|

Monthly maintenance/management @30% of rent |

£360 | |

|

Net income before tax |

£780 | |

|

Tax @ 40% (rising to 42% in April 2027) |

£312 | |

|

Mortgage interest |

£540 | |

|

Mortgage interest tax credit @20% |

£108 | |

|

Net income after tax |

£36 | |

|

Net rental yield after tax pa. |

0.2% | |

|

Yield on Investor’s capital pa. |

0.9% |

Source: Albion assumptions and estimates 2025 – provided as a basic generic example only.

Buy-to-let advocates may dispute the numbers, and it is acknowledged that rental yields can vary quite widely across the UK, as do maintenance costs and occupancy rates. The numbers above are highly sensitive to inputs.

However, it is a reasonable framework for making better informed decisions. On these numbers, an investor with no mortgage would have received a net yield after tax of around 3% pa. on their capital, this is a lot of effort to barely even beat inflation in good years, and not to have beaten inflation at all since the pandemic.

What is interesting about the numbers in the example is that if the mortgage interest rate is raised by just 0.5% then the net yield after tax is near enough zero, before inflation. It’s a common misconception that rents automatically rise alongside interest rates. History tells a different story. During the early 1990s property slump, mortgage rates soared to 14%, leaving many landlords scrambling to cover shortfalls out of their own pocket.

Take the worked example above: in 1991, a geared buy-to-let investor would have faced an extra £900 a month just to plug the gap between rent received and mortgage costs. For many, this financial strain was compounded by negative equity, as house prices slid. From the market bottom in 1993, it took more than five years just to get back to pre-crash levels in nominal terms and even longer once inflation was factored in. Some investors simply couldn’t hang on, selling at a loss and fuelling further price falls.

Given the very low net yields on offer today, buy-to-let is, in effect, a strategy reliant on price appreciation for its long-term success.

Thinking like a smart investor

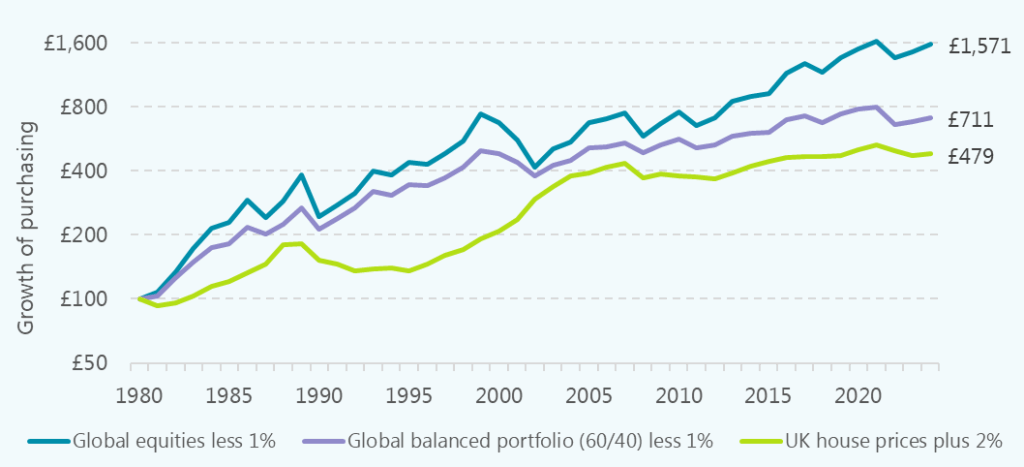

An astute investor will look at an asset class dispassionately and consistently, neither looking solely at yield or capital gain, but on a total return basis. To make a better-informed comparison, and to try and level out the playing field, if we assume a generous net post-tax yield of 2% on an ungeared buy-to-let investment and add this to the price return of the UK house price series, we can get a rough picture of how it has performed against other more traditional investment portfolios. Costs of 1% per annum have been deducted from the traditional portfolios for fairer comparison. No initial set-up costs for the buy-to-let strategy have been deducted, even though these can be material. The outcome is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Buy-to-let versus traditional portfolios – simulated strategies after inflation 1981-2024

Data source: See endnote[8].

The graph above is based on average UK property price growth plus a 2% yield, most individual’s experience will deviate from the average and in many cases significantly. Some will experience far better than average results and some far worse, this is the nature of risk one takes on when investing in single, or a small number of, assets. With equities and balanced portfolio figures, however, what you see is what you get. These figures are illustrative of the real returns experience of someone who invested in these ways in the 1980s.

Stories of outsized returns dominate the media landscape far more than those who’s experience was ‘average’, or even those who suffered far worse. The main point is this: Investors should consider whether the risk involved in pursuing such outsized returns is worth the potential consequences of property investment not going to plan, especially when, looking at averages, the expected returns do not stack up to alternatives.

Pensions over property?

It is easy to see why pensions have come in for such a bashing, mis-selling scandals and high fees have previously tainted their image. More recently the announcement that pensions will come into the inheritance tax net in 2027 haven’t helped. However, pensions were never intended to be an inheritance tax vehicle, they exist chiefly for securing a successful retirement.

Since the introduction of new regulations over the years, pension freedoms in 2015 and the removal of the lifetime allowance in 2024, pensions have become an even more invaluable tool in retirement planning.

The Triple Tax Advantage

Pensions enjoy a unique threefold tax benefit:

- Tax relief on contributions: Receiving immediate tax relief of usually 20–45% depending on income. For a higher rate taxpayer, a £50,000 pension contribution is worth £66,667 on a gross basis. This is in contrast to buy-to-let investment, which is often made from savings amassed from after-tax income.

- Tax-free growth inside the pension: Investments grow free of income and capital gains tax for as long as they stay in the wrapper.

- Tax-efficient withdrawals: Up to 25% of a pot (capped at £268,275 over all pensions) can usually be taken tax-free, with the balance taxed as income, often at lower rates in retirement.

This combination—relief on the way in, growth sheltered on the inside, and reduced tax on the way out—is hard to match elsewhere.

Not only this, but pension contributions are counted by HMRC when working out a taxpayer’s adjusted net income. Because of this, there are opportunities to utilise pension contributions to reduce the higher or additional rate tax paid or even drop out of a tax band altogether, those with incomes over £100,000 may be able to avoid some or all of the personal allowance taper, what some refer to as the ‘60% tax trap.’

Pension sceptics may point to the disappointing performance of the UK equity market over past decade or so as evidence. Yet sensible investors will know that global diversification is important. In fact, over the past 20 years the broad global markets have returned around 10% per year on average[9]. This rate of growth would double capital every seven years and quadruple it in fourteen. For a retirement vehicle designed to run over decades, those are exceptional results.

Property and pension are not mutually exclusive

Property may have a place to play in investors’ wider wealth plans, perhaps through an allocation to global commercial property as part of a well-balanced and diversified traditional investment fund.

Perhaps the biggest risk of the buy-to-let market is the concentration of risk in not just one narrow asset class – residential property – but in one house or flat, on one street in one town. This lack of diversification is an unattractive attribute for a plan to deliver wealth and happiness in retirement.

Conclusion – pension funds are a core retirement pillar

Ungeared buy-to-let resembles running a small business: one that requires time, attention, and constant maintenance just for expected returns that sit somewhere between bonds and equities. Add a mortgage into the mix, and the risks amplify dramatically. What’s often sold as a “deposit-like” alternative is in reality a highly leveraged, illiquid venture.

Buy-to-let is certainly not a quick or riskless road to riches. It comes with costs, regulation, tax burdens, and the everyday hassles of running a business. Some enjoy the challenge and even find it rewarding. For others, it becomes a drain on time, energy, and peace of mind.

By contrast, pensions, especially when invested through globally diversified portfolios, offer powerful tax breaks, long-term growth potential, and the freedom to pursue retirement on your own terms.

In the end, the real value of a pension isn’t just in the numbers, it’s in the time and headspace it frees up to spend on what matters most. Because when it comes to retirement, who really wants to be at the beck and call of a tenant with a broken washing machine?

Risk Warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes for UK residents. It should not be considered investment advice, an offer of any security for sale nor a recommendation of any particular security, strategy, platform or investment product. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily the Firm. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

[1] Bank of England © SONIA and UK CPI. Data to Apr-25.

[2] ONS © Private rent and house prices, UK: April 2025.

[3] Recent data estimated maintenance costs in 2024 at an average of 0.5% of average UK house price. The Cost of Being a UK Landlord | Towergate Insurance

[4] Buy to Let Mortgage Rates | BTL Interest Rates – HSBC UK

[5] Tax relief for residential landlords: how it’s worked out – GOV.UK

[6] For the financially astute it would make sense to calculate the internal rate of return that any buy to let property opportunity could deliver from all of the cash flows involved and to see where the risks and return truly lies.

[7] UK Buy-To-Let Yield Map 2024 | Verta Property Group

[8] Global equities Albion World Stock Market Index (AWSMI). Balanced (60/40) = 60% ‘Global equities’, 40% Albion 2.5Y UK Constant Maturity Bond Index. Costs of 1% have been deducted from the ‘traditional’ portfolios and portfolios were rebalanced back to the original mix once a year. UK house prices = Nationwide House Price Index.

[9] Vanguard Global Stock Index Fund (IE00B03HD209). Data to Apr-25 in GBP. Doubling your money figures calculated based on the ‘rule of 72’.

Share this content